Osurbia

Os (NO) – Lauréat

DONNÉES DE L'ÉQUIPE

Représentant d'équipe : Gonzalo Jose López Garrido (ES) – architecte ; Associées : Alicia Hernanz Pérez (ES), Diana Cristóbal Olave (ES), Tania Oramas Dorta (ES) – architectes

Brooklyn – USA

team@knitknotarchitecture.com – www.knitknotarchitecture.com

Voir la liste complète des portraits ici

Voir la page du site ici

D. Cristóbal Olave, A. Hernanz Pérez, G. J. López Garrido & T. Oramas Dorta

INTERVIEW en anglais

Cliquer sur les images pour les agrandir

1. How did you form the team for the competition?

We entered Europan 13 as an initiative of our collective, knitknot architecture. Knitknot architecture was set up back in 2013 as the result of a series of circumstances that enabled people pursuing different professional interests (i.e. architectural practice, urbanism, research, teaching, etc.) and based in different cities (i.e. London, New York and L.A.) to work together on the basis of the understanding that, in a time marked by people’s hyper-mobility and hyper-connectivity, new ways of professional association that are no longer bounded to a ‘physical space’ are possible. From that moment we have developed a range of projects: from research projects to architectural competitions, from non-profit schemes to building commissions; by taking advantage of new communication and digital information systems as key elements of our working processes. This working methodology has enabled us to share knowledge, mobilize skills, cooperate with each other and take initiatives in a non-hierarchical, dynamic and flexible manner.

2. How do you define the main issue of your project, and how did you answer on this session main topic: Adaptability through Self-Organization, Sharing and/or Project (Process)?

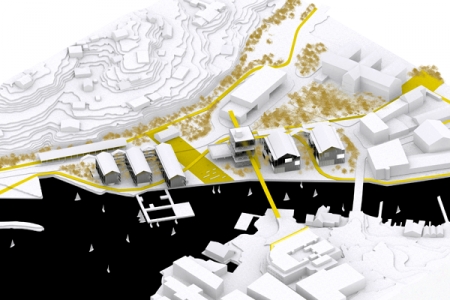

In the case of Os adaptability is a crucial issue, since the municipality has faced a two-fold increase in its population within a relatively short period of time (i.e. 25 years). This brings issues related to physical adaptability such as the construction of new infrastructures in the area, or the development of an urban fabric capable of housing the new population and its daily activities. But most importantly, it brings questions related to social and economic adaptability such as making Os resilient to these significant changes while preserving its identity. On the other hand, the idea of ‘sharing’ becomes a key driver of the proposal, derived from the fact that a site currently privately-owned and located in a privileged position within the town is to become open to all citizens and visitors.

Our proposal deals with these issues by enhancing Os’s identity through the reconceptualization of the idea of ‘suburbia’ and the redefinition of five recognizable suburban types within the town: the single dwelling, the parking lot, the mall, the filling station and what we refer to as ‘suburbia beyond the dwelling’, i.e. the socio-economic conditions of the site. By working with existing and identifiable elements we aim at creating unique and site-specific urban conditions within a new urban paradigm driven by sustainable development.

Additionally, the issue of sharing is addressed by introducing a sixth urban type, ‘the strip’, which provides unity and coherence. This type ensures continuity not only within the new development, but also to the whole urban setting (i.e. the existing commercial center, the area around the Oseana culture house, existing areas of single family houses, etc.). This spatial continuity, together with the proposition of a rich mix-use development, seeks generate a ‘space of sharing’ for locals and visitors, young and elderly, students and professionals, and so on.

3. How did this issue and the questions raised by the site mutation meet?

The issue of adaptability has been linked to suburban town centers by different authors (e.g. ‘Non- Plan: an experiment in freedom, 1969’). As opposed to an urban model of positive development, where design is highly regulated, ‘suburban development’ has been characterized by building solutions or patterns that comply with the actual needs of users. The ability of this urban fabric to suit people’s various purposes throughout time has allowed the generation of multiplicity of activities and uses, due to their ability to easily adapt to social and economic change. With this spirit, our project proposes a series of ‘open typologies’ or ‘generic structures’ within recognizable and ‘symbolic types’, which are capable of adapting to different users, economic constraints and inhabitant’s needs over time.

4. Have you treated this issue previously? What were the reference projects that inspired yours?

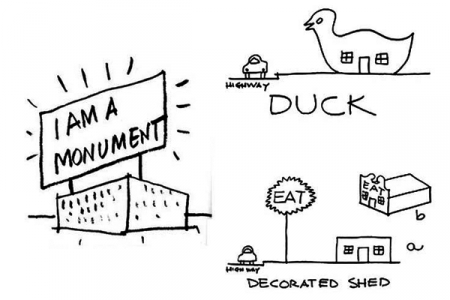

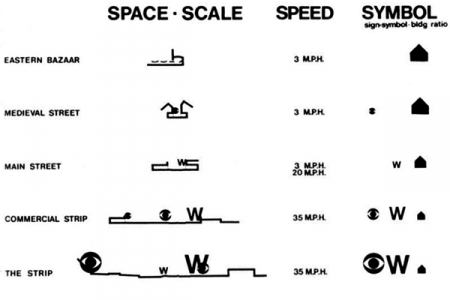

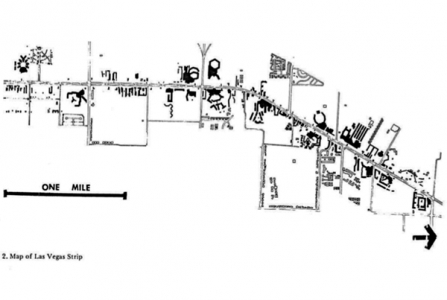

‘Learning from Las Vegas (1972) by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour has been one of the main inspirations for our project. These authors urge architects to learn-from-what’s-around-them; to look at the everyday landscape, the popular culture and the values of ‘common’ people as a springboard for authentic building in contemporary times. These ideas inspired us to look at the existing landscape and culture in Os and try to learn from its built forms and associated symbolism. We realized that many of the suburban elements that Venturi et al. had identified in Las Vegas’s landscape were also present in Os, albeit in a smaller scale: the strip, the parking lot, the filling station, etc. Going beyond the analytical standpoint of Venturi and his friends, our proposal seeks to re-appropriate and re-define those typologies in a context where issues of sustainability, integration vs. segregation, identity, etc., are at the forefront of the current development of our cities.

All images hereunder are taken from “Learning from Las Vegas”, by Robert Venturi, Steven Izenour, Denise Scott Brown (1972)

5. Today –at the era of economic crisis and sustainability– the urban-architectural project should reconsider its production method in time; how did you integrate this issue in your project?

Existing elements in Os, such as the old train station and the hall for wagons, have evolved over time to adapt to new uses (i.e. art gallery, workshop and exhibition spaces, etc.) partly thanks to their typological flexibility. These have as a consequence become a fundamental part of Os’s history, landscape and identity. Likewise, our project redefines the proposed categories (i.e. strip, dwelling, parking lot, mall, filling station, etc.) by placing flexibility at the heart of the process in a manner that the new proposed structures can easily adapt to new uses and ways of living and evolve over time, albeit preserving their identity.

6. Is it the first time you have been awarded a prize at Europan? How could this help you in your professional career?

Europan 12 was the very first competition we entered as knitknot architecture. We consider Europan to be one of the most interesting competitions in Europe due to its focus on experimental and innovative discussion, not only in terms of urban and architectural processes, but also regarding socio-cultural and economic phenomena associated to the design of our built environment. On the other hand, we consider Europan to be one of the best and few platforms for young architects’ work to be recognized. We didn’t get any prize at that time, but we learnt extensively along the design process, which encourage us to enter the competition again for the Europan 13.

Winning the first prize in a competition of this kind is a great privilege for knitknot architecture. Obtaining the recognition from a well-established organization such as Europan, provides great visibility to our collective and our work, and encourages us to undertake new projects. An additional boost to our professional career would certainly come from this project or part of it becoming an actual commission. We believe this would allow us to truly engage with the area and its community, and become part of a project we consider as crucial for the future development of Os and its citizens.