Open Space Fabric

Genève (CH) – Mentionné

DONNÉES DE L'ÉQUIPE

Représentant d'équipe : Miguel González Castro (ES) – architecte ; Associés : Marta de las Heras Martínez (ES), Laura Martínez Alonso (ES), María Núñez Rodríguez (ES) – architectes ; Anibal Hernández Sánchez (ES) – anthropologue

Pinar de Somosaguas 112, 28223 Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid – España

+34 640 518 383 – patatafritapublica@gmail.com – openspacefabric.tumblr.com

Voir la liste complète des portraits ici

Voir la page du site ici

M. Núñez Rodríguez, L. Martínez Alonso, M. de las Heras Martínez, M. González Castro & A. Hernández Sánchez

INTERVIEW en anglais

Cliquer sur les images pour les agrandir

1. How did you form the team for the competition?

We are an informal, flexible and passionate collective of young professionals and activists from different fields, from Architecture and Urbanism to Sociology and Anthropology. We work on different projects related to issues of sustainability, mobility, self-management, participation and resilience from the perspective of de-growth and social equity. For Europan 13 we saw an opportunity to put into practice our ideas on how to build and think the city.

2. How do you define the main issue of your project, and how did you answer on this session main topic: Adaptability through Self-Organization, Sharing and/or Project (Process)?

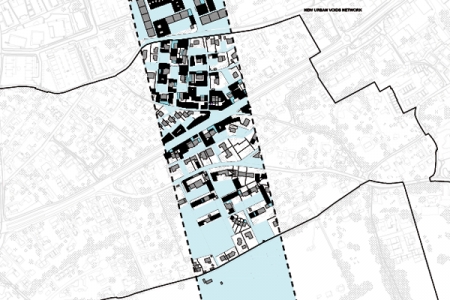

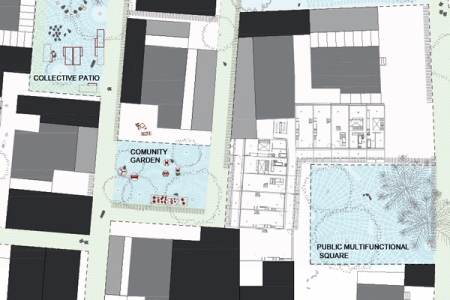

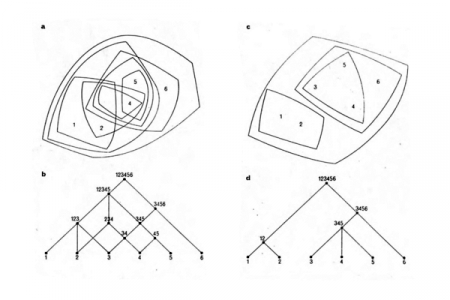

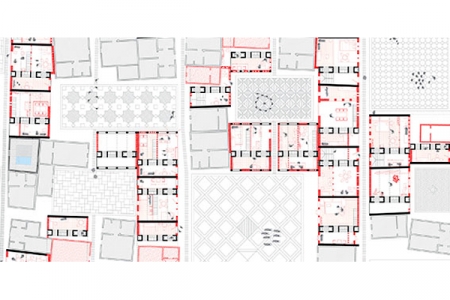

Our main goal was to create a model for participation, self-management and densification of the site respecting the identity of the place and its ecological value, while at the same time creating opportunities to turn under-used and privatised spaces into shared, common and productive spaces – i.e. spaces where people have the chance and the right to produce whatever they think they need to make their lives better in any sense, and to do it collectively. We think this approach can turn Onex into a city in adaptation to changing economic and social conditions with its inhabitants as main leaders of the transformation.

3. How did this issue and the questions raised by the site mutation meet?

The site is quite a challenge and that is why we chose it. This kind of suburban dispersed housing areas are always difficult to deal with. There are disadvantages like too low density in terms of people, jobs and services or less opportunities for social interaction; and actual sustainability problems like mobility, dependence on more densely populated areas and low diversity of uses. At the same time, these areas tend to have better living conditions, high quality housing, environmental and ecological values... Our main concern was to endorse the cons without compromising the pros. And that is what we tried to do respecting the environmental context and the built environment as much as possible and promoting shared, productive and open spaces surrounded by higher density housing.

4. Have you treated this issue previously? What were the reference projects that inspired yours?

We are always dealing with issues of adaptability (although we more often talk about resilience), self-organization and self-management, and the commons. We have already presented different projects with the same perspective: ‘Benimaclet y la Huerta’, ‘Valencia Free Bike Rental’ or ‘Habitat en Casablanca’. And we always like to mention some people and projects that inspire us like Christopher Alexander, Ivan Illich or John Holloway; the group n’UNDO or Salotto Buono”s “Manual of Decolonization” project.

5. Today –at the era of economic crisis and sustainability– the urban-architectural project should reconsider its production method in time; how did you integrate this issue in your project?

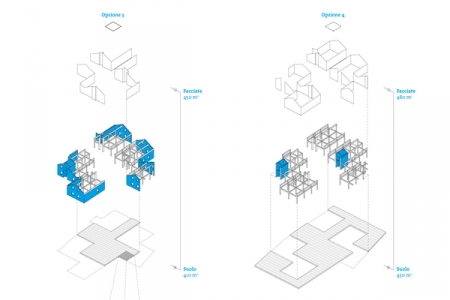

Well, we actually think that the economic and the ecological crisis are deeply connected; therefore urban-architectural projects (and everybody else actually) should reconsider goals, methods and priorities. We integrated three main aspects to tackle all these issues that can be progressively implemented. First, we wanted to conserve as much of the ecological value of the site as possible. Not only because we think that the whole foundation of resilience, adaptability and any sustainable economy depends on it, but also because it is part of the identity of the community, and having a strong collective identity is crucial for resilience. Second, we tried to densify building on what is already in place, trying to take advantage of the existing built infrastructure. In this way, the proposal re-uses and reduces the need for new materials. Finally we wanted to create shared spaces open to different kinds of property and management statuses, but always aiming at creating places that not only have leisure or social purposes, but also creative spaces where people can grow food, repair bikes or create whatever they want. This is how communities should start becoming resilient in a context of crisis.

6. Is it the first time you have been awarded a prize at Europan? How could this help you in your professional career?

One of our team members was awarded as runner-up in Europan 12 but it is the first time we have been rewarded as a team and we are very glad about it! First but not last!

We are proud, but what is actually relevant for us is how the construction of resilient communities based on sustainable and self-managed approaches can be helpful when dealing with the aforementioned context of multiple crisis. Geneva might have a privileged position to lead and innovate in the transformations of cities towards resilience and self-management in the city. So there are chances of change, which is quite encouraging for us, not only as technicians but also as neighbours, we find this shows a hopeful turning point in urban growing politics, where new voices will be considered.